watch this space

During my permitted “once a day” exercise/dog walk I’ve been enjoying listening to the BBC World Service’s 13 Minutes to the Moon podcast, written by Kevin Fong. The current (second) series describes the Apollo 13 mission, in which the astronauts and their mission control team battled to cope with the catastrophic aftermath of an explosion in a fuel cell which ended their hopes of a lunar landing and gave them a very slim chance of returning home safely.

Apollo is a timely focus in the current climate. In Greek mythology, Apollo was the god of light, knowledge, music, poetry and healing. Amongst other qualities, he is strongly associated with the health and education of children.

One head teacher I work closely with described the Covid-19 crisis as our “Apollo 13” moment, and this Easter weekend marks the 50thanniversary of the Apollo 13 mission. There is a sense in which we are developing solutions as we go along, but might we also learn from Apollo to cope with the changes and challenges we are facing and so that we might improve the quality of the education we provide in the long term?

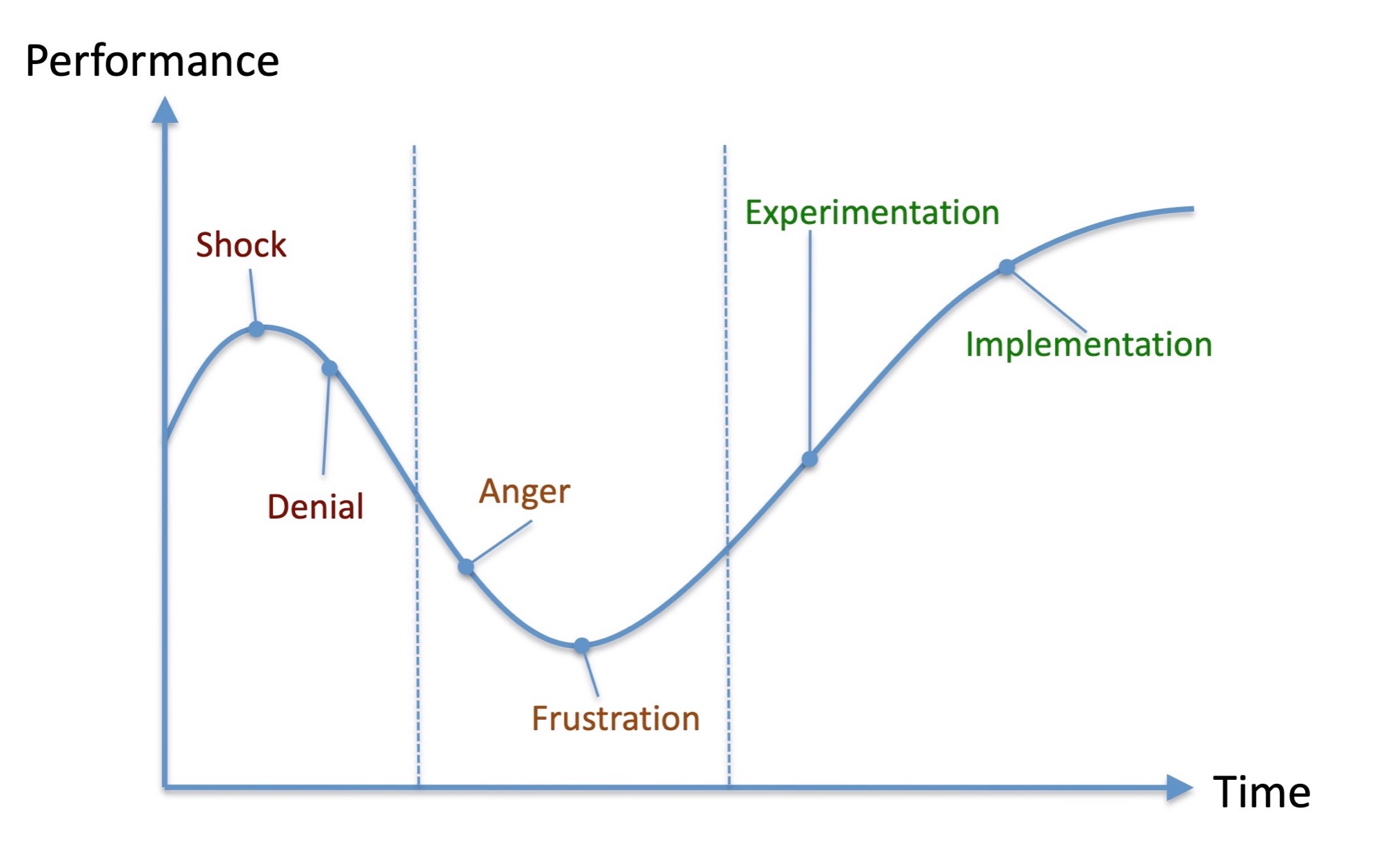

The process of change, whether externally or internally determined, often follows a similar pattern. Psychologist Elizabeth Kubler-Ross initially proposed it in 1969 as a series of steps she had observed in terminally ill patients. Although its evidence-base is somewhat limited, it has become a favoured model in change-management theory, and appears in many different versions.

This process can be separated into 3 distinct sections. It’s instructional to notice how the Apollo 13 team went through these phases too.

Stage 1 - “We’ve got a problem”

The first stage is typified by shock and denial. When the explosion happened on Apollo 13, mission control’s initial response was one of denial. They assumed they must have an instrumentation error. As the severity of the situation became clear, denial led to disbelief. Flight controller Sy Liebergot stated he couldn’t believe that a titanium oxygen tank had exploded:

“If things got real tense – if there was a bad problem, you could see us grabbing one handle. If it was a real bad problem, you’d be grabbing both handles. You know you get the cold feeling in the pit of your stomach, like, this is really bad, but you can’t get up and go home. But this was not an option.”

Moving through this stage requires information with clear, direct communication. People want answers to their concerns, but these need to be carefully managed.

On an Apollo mission, all communication with the spacecraft was through one dedicated colleague, known as CAPCOM. This would be a trained astronaut who might envisage the situation the crew found themselves in. This single channel ensured that communication was timely, clear and specific. CAPCOM could also ensure that the messages were positive and proactive. For example, rather than the expletive-ridden, frank analysis provided by one flight controller, CAPCOM communicated:

“We’ve got lots and lots of people working on this. We’ll get you some dope as soon as we have it and you’ll be the first ones to know.”

Stage 2 - “Is there anything we can trust?”

In the second stage, anger and frustration resulting from the situation are often prevalent. The reality becomes clear, and may lead to resentment, depression and fear.

“What do you think we’ve got in the spacecraft that’s good?”

On Apollo 13 flight director Gene Kranz realised that he needed to stop analysing the problem and start identifying the thing he knew were working well.

Moving through this phase requires clear planning, support and encouragement. This planning helps avoid chaotic response that might otherwise result at a time of low productivity. It can also require time, particularly in a large organization as members of staff may move along the change curve at different rates. Leaders need to anticipate the change and provide the mechanisms for others to move along it at appropriate rates. As Kevin Fong writes:

“Keeping control of your team in the face of something so chaotic is tough. Without proper discipline things will disintegrate. This is the genius of Kranz’s leadership. He finds a way to force his flight controllers to stop, reset their approach and start again from fresh.”

Stage 3 – “Start handing over”

Fong also describes how Kranz had the discipline to relinquish control to the incoming team at mission control, rather be tempted to make all the decisions himself despite the pressures and responsibility, recalling Kranz’s words:

“A fresh team is probably going to thinking clearer. The rest of us can continue working in support of that new team.”

Characteristics of the third and final stage of change leadership are acceptance, exploration and experimentation. Carefully led and managed these result in integration and improvement. Initially it’s important to capitalise on the ideas of the teamthrough encouraging creative thinking. Glynn Lunny, who replaced Kranz part way through the crisis, was clear that he needed to ask his flight controllers for their recommendations, whilst remaining calm and taking responsibility for the external pressures of time. Fong states:

“Survival depends on an option which is not in the flight manual. This is as close to a leap of faith as NASA will ever make. Mission operations are supposed to run on carefully prepared checklists with well-rehearsed procedures. Improvisation is something to be wary of.”

Schools are also closely associated with procedures and dislike improvisation. At a time of crisis, moving through this stage 3 requires both training and decisionswith the recognition that there may be no precedent for required actions. Training helps get the best out of everyone rather than accepting the status quo, and again may take time. Having explored a variety of options, at this stage decision making needs to be clear and well communicated.

Back to normality

I’m aware that many of our children won’t know the story of the Apollo 13 mission, so I won’t give away the ending here, but there is one other timely story to tell. The original flight crew included the astronaut Ken Mattingly. During training all crew members had been exposed to the rubella virus through a fellow astronaut. Mattingly was the only one not to be immune from the disease, and was forced to withdraw from the mission.

As the emergency unfolded, Mattingly found himself called upon to try to develop a procedure for ensuring the safe return of his fellow astronauts through experimentation in the simulator. His expertise proved invaluable – you might say that he undertook extreme home working!

Where do you think you are currently on the change leadership curve? Where are the members of your team? What approach to you need to take to ensure that, following this crisis period, our practice and procedures are stronger and more effective than before? Which of the god Apollo’s qualities do you most need now?

And whatever your situation over the next few weeks, If you find yourself with some spare time in the next week (!) and are looking for a great family movie, you could do worse than Apollo 13.

Jez Bennett, 28/03/20

Quotations in this article are taken from the podcast 13 minutes to the moon.